Photo c/o Symphony Space

Hop off the red line at 96th and Broadway and you’re at Symphony Space; a nationally acclaimed performing arts organization on the Upper West Side. A few strides down 95th Street and you’ve landed at its modest 160 seat Thalia, a once-legendary arthouse cinema made iconic in Annie Hall. Above the Symphony Space marquee is billionaire Peter Norton’s name. Above The Thalia marquee is Leonard Nimoy’s name. Mr. Norton invented the world’s most famous antivirus software and Mr. Nimoy invented Spock. Symphony Space’s not-so-modest 760 seat theater (larger than the American Airlines Theatre) is called the Peter Jay Sharp Theatre. Mr. Sharp was a hotel and real estate mogul whose philanthropic name-brand marks theaters at BAM, Lincoln Center and Playwrights Horizons.

Advertisement

These people reinforced Symphony Space’s influence and infrastructure and forged it into an anchor of national culture. It is a reminder that despite our vacant shop windows and high-rise luxury construction sites, the arts reverberate throughout our Upper West Side community. But before the money or public radio timeslots, there was only an idea and people. In 1978, three next door neighbors would reshape New York City’s cultural landscape for decades to come. They are Isaiah Sheffer, Ethel Sheffer and Allan Miller.

Ethel and Isaiah were married and living down the hall from Allan, a professor, conductor, and academy award-winning filmmaker. Isaiah taught acting at Columbia University while Ethel, who taught political science at Brooklyn College, would soon embark on a prolific career in urban planning. The three were friends, neighbors, colleagues, and Upper West Siders.

Read More: The Lincoln Arcade: An Artist Incubator

Throughout the 1970s, New York City’s homicide rate was 3-4 times higher than it is today. Severe economic problems, a reduced police force and the dissolving of mental institutions – coupled with a high volume of single room occupancies – led to the Upper West Side’s emergence as a hub for dangerous activity and a magnet for mentally ill and impoverished people. Simultaneously, it was a place of concentrated wealth. These two extreme realities lived side by side, sharing Broadway.

As Ethel was walking down Broadway one afternoon, she glanced across the street and witnessed a woman pull up her skirt and defecate on the median. Disturbed by the disparity in her neighborhood, Ethel went home and began assembling a group of friends and colleagues. Together, they established Blocks for a Better Broadway – a community organization designed to improve conditions along Broadway between 96th and 86th streets.

Read More: The Upper West Side in the Mid-1940s

Meanwhile, Allan was conducting for the American Symphony Orchestra and sought to produce a concert on the Upper West Side. Traveling from his apartment to theirs, he stepped across the hall to scheme with the Sheffers.

Advertisement

Isaiah and Allan had collaborated before, but they didn’t know where to hold this event. Having begun her work in the community, Ethel suggested the old Symphony Theater. This was not an obvious choice. The Symphony Theater was a dilapidated, grungy, dirty space. Originally a fruit, vegetable, and fish marketplace, it later morphed into a skating rink and by 1977, it had become a shabby destination for amateur boxing and wrestling matches.

Allan Miller and Isaiah Sheffer, 1978. Photo c/o Symphony Space

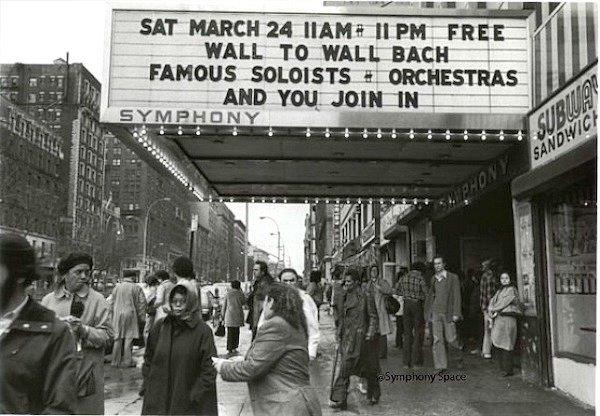

On Saturday, January 7, 1978, Isaiah and Allen rented the Symphony Theater for $300. Their idea was “Wall to Wall Bach,” a 12 hour event in which amateur musicians could play alongside professionals for an epic day of classical music.

Photo c/o Symphony Space

On paper, it sounded like a preposterous idea. It was below freezing, the venue was decrepit and nothing like this had ever been attempted on the Upper West Side. And yet, between 11am and 11pm, somewhere between seven and eight thousand people showed up.

When the musicians began to play, Allen and Isaiah were amazed to discover that this timeworn space had excellent acoustics. As the historic affair concluded, audiences picked up sheet music and sang Bach’s Mass in B Minor. Astounded at what they had created, weeping at the profound community experience, Isaiah looked around at a symphony of singing Upper West Siders and said to himself, “We’ve got to take over this joint.” And they did.