Since the inception of the free market in the United States, there have been numerous Wall-Street inspired economic “panics” that turned daily life on its head. Prior to the Great Depression, the most notable panic event occurred in 1837, and was fueled in large part by a shortage in bread – both the flour-based kind and the currency kind.

Economic discontent was creeping towards despair by the end of 1836. Manhattanites trying to make a living were met with soaring prices that made it not only difficult to make ends meet, but nearly impossible for those starting out to get anywhere. “Since December, the price for flour had soared from $4.87 to $12.00 per barrel, and the price of pork had climbed from $13.00 per barrel to $24.50,” according to Burrows and Wallace’s Gotham.

Advertisement

Discontent turned to violence on February 13, 1837, when approximately 5,000 New Yorkers took to City Hall Park to demand price decreases for basic necessities like food and coal. Mayor Cornelius Lawrence tried to restore calm, but was “shouted down, barraged with stones, and compelled to retreat for his life.” Sparked by rumors of dealers hoarding flour, the angry crowd stormed the headquarters of Eli Hart & Company, a New York City flour merchant. Rioters “smashed desks and scattered papers … hurled hundreds of barrels of flour and sacks of wheat to the street below.” Later attempts at violence were quelled by common sense and law enforcement. Though the violence ceased, the worst was yet to come.

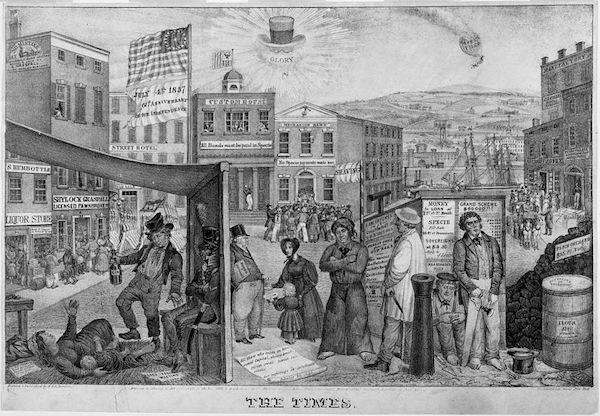

An 1837 caricature blames Andrew Jackson for hard times. c/o Edward Williams Clay [Public domain]

March 15, known as the Ides of March, was considered the deadline to settle debts in ancient Rome. Historically, this date has been associated with bad luck because it marks the anniversary of Julius Caesar’s brutal murder. In New York City in 1837, the Ides of March was the tipping point for what would be a nationwide recession lasting more than six years.

Get The Upper West Side Newsletter

Numerous southern merchants defaulted on payments owed to their Manhattan creditors and quickly caused 93 firms to collapse by April 8. The number rose to 128 three days later and totaled more than 250 by month’s end. A domino effect was felt all over the city.

Construction projects in all sectors were halted including transportation initiatives like the Long Island Railroad. Housing demands could not meet the supply. The stock market crumbled, causing even more businesses to fold. “Virtually all of New York’s major clothing firms floundered in 1837.” Banks and lending firms halted lending, including loans to the city’s richest citizens like the Astor family.

As the banks started to demand payment for outstanding loans, the city’s “poor and laboring classes” demanded the return of their deposits. One bank president died, allegedly under suspicious circumstances. “On May 10, all twenty-three of Manhattan’s banks announced that they would henceforth refuse to exchange specie for paper … Within 24 hours, most banks in the Northeast had stopped gold and silver payments.”

Check out our partner site @ eastsidefeed.com

By the end of May, the city was a ghost town. The currency shortage shut everything down. “No goods are selling, no business stirring, no boxes encumber the sidewalks of Pearl Street,” wrote former mayor Philip Hone according to Gotham. No one and no thing was exempt from this new economic depression.

Advertisement

How was the Upper West Side impacted? Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a definitive answer, though it seems unlikely that it did not suffer like the rest of the city and, eventually, the country. What is known is that the plunging real estate market hit the UWS hard in a matter of roughly seven months. “Landowners near Bloomingdale Village had been getting $480 an acre in September 1836; by April 1837 … they were lucky to clear fifty dollars,” Gotham reports.

Photo c/o New York Public Library.

In the 1830s, the Upper West Side was mostly farmland, divided into three main villages – Harsenville, Bloomingdale, and Strycker’s Bay. The bucolic nature of the neighborhood at the time did not lend itself to a teeming hub of commerce, particularly with most of the city’s industrial sects still located in the lower part of Manhattan. The respective farm owners earned income from their crop (mostly tobacco).

READ MORE: THE BLOOMINGDALE INSANE ASYLUM

Near the end of the 1830s, the estates of two prominent Upper West Siders were placed up for grabs after decades and decades of family ownership. “Land values crashed and overextended investors lost thousands of acres to their creditors prompting a second mass transfer of land.”

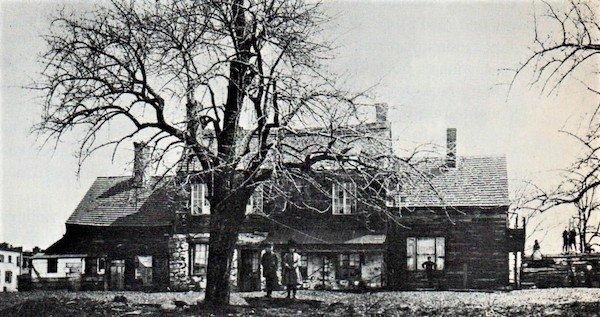

Jacob Harsen settled the land that stretched from today’s Central Park West to the Hudson River between 69th to 73rd Streets as a family tobacco farm in the mid-1700s. When he passed away in 1835, his heirs “leased out at least part of their inheritance which included a store, some lots and a piece of pasture” by May 1839. The pasture’s leaseholder then subleased the pasture for a number of years.

The Harsen homestead, via NY-Historical Society.

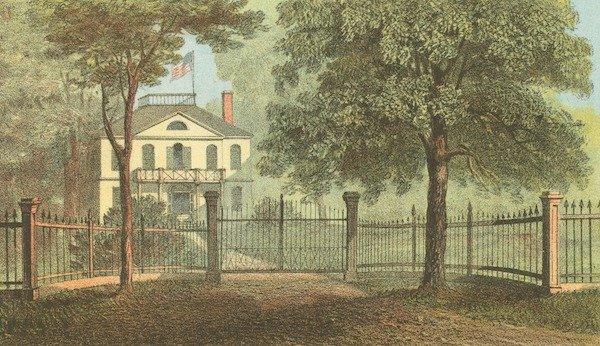

John Clendening – whose Sharon Farm occupied much of the upper reaches of Bloomingdale Village including the family home located at today’s West 104th Street and Columbus Avenue – passed away in February 1836. His Upper West Side estate was subsequently sold due to the “family’s financial losses, sustained when the Second United States Bank failed,” the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group writes.

Clendening Mansion, via NYPL

He was one of the largest investors in the Second United States Bank, whose charter was set to expire in 1836. President Andrew Jackson, notorious for his anti-bank politics, vetoed the bill to re-charter in 1832, and caused the bank to privatize under Pennsylvania law in 1836.

Advertisement

“A shortage of hard currency followed, causing the ‘Panic of 1837,’ which lasted some seven years. The Bank suspended payments in 1839 and was liquidated in 1841. John Clendening’s death came just as the Bank’s charter was ending – although well before his death he knew it would cease. There’s no way of knowing of his efforts to save his fortune.”

The country ultimately recovered and so too did the Upper West Side. The concept of public housing was born from this crisis as was today’s credit ratings industry. The Croton Aqueduct was completed by 1842 and with it came a fresh supply of clean water. Urbanization continued its uptown expanse along with Manhattan’s street grid and, eventually, the Subway system. “Booming economic conditions in the 1840s, coupled with immigration, restored profitability and housing starts,” according to Robert A. Margo in his 1996 article titled “The Rental Price of Housing in New York City, 1830-1860” as it appeared in The Journal of Economic History.

Just like the 1792, 1796 and 1819 panics that preceded the one in 1837, similar financial imbroglios followed in 1857, 1861, 1873, 1893, 1896, 1901, 1907, and 1910. The stock market crashed in 1929 causing the ten-year long Great Depression. “Then we really didn’t experience anything comparable until 2007,” according to the New York Times, an accomplishment many credit to the 1913 creation of the Federal Reserve.

READ MORE: A SHANTY TOWN ALONG THE HUDSON RIVER

However, excluding 2007, the aforementioned statistic does not factor in the recessions since World War II: 1945, 1948, 1953, 1957, 1960, 1969, 1973, 1980, 1981, 1990, and 2001. There was also a recession in 2020, when “unemployment [was] at levels unseen since the Great Depression — the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialized world.”

While the frequency of these economic downturns may seem staggering, there is some good news. According to History.com, “on average, America’s post-war recessions have lasted only 10 months, while periods of expansion have lasted 57 months.” The better news for us as New Yorkers is that we always seem to manage to not only get through the hard times, but we lead by coming out ahead in the end.