“Bloomingdale Village, 1867 in New York City” – via New York Public Library

It’s hard to imagine the Upper West Side of long ago, untouched and undeveloped. Thick woods, rolling hills, endless greenery. Former battlegrounds of the Revolutionary and Civil Wars and the War of 1812. Redcoats wandering around like they owned the place while George Washington led the country’s fight for independence. Neighborhoods largely unreachable to the public, and, like Strycker’s Bay, most readily accessible by boat.

Advertisement

Like Harsenville, Strycker’s Bay was part of the Bloomingdale District and, according to Peter Salwen’s Upper West Side Story, “the heart of the wealthy suburb.”

The Strycker family (Strijcker in the original Dutch and anglicized as Striker and Stryker) hailed from the Netherlands, an esteemed bunch regarded as a step below royalty. In 1643, brothers Jan and Jacobus Strijcker were granted land in New Amsterdam by the States-General of the Netherlands on the condition that they take twelve other families at their own expense. Eight years later, Jacobus set sail for the new world and was followed by Jan the following year. However, it was Jacobus’ great grandson Garret who would ultimately settle on the land that would bear his name.

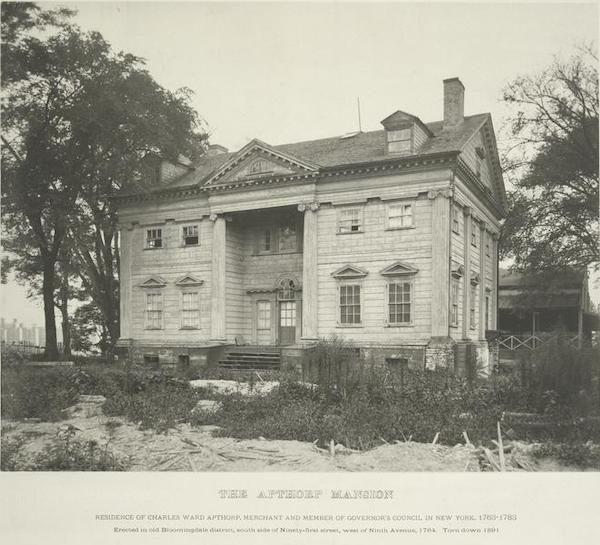

Garret, who changed his name to Gerrit Striker, purchased fifty acres of land from Charles Ward Apthorp, namesake of the historic Apthorp condominium, on August 8, 1764 for £500. Bordered by a 60-acre estate owned by merchant John McVickar around 86th Street and land held by Humphrey Jones northwards to 96th Street, Strycker’s Bay began “at the head of a certain cove on the easterly side of the North River” and extended over to Bloomingdale Road, the present-day Broadway.

Though the Strycker family farmhouse was located at 97th Street and Columbus Avenue, the area was known for an inlet or bay accessible by ferry to and from the offerings of downtown Manhattan. Striker’s wharf was used by the rebels during the American Revolution to bring supplies onto the island. The Striker’s home, like their 91st Street neighbor Apthorp, played host to British troops. However, Apthorp may have lent his homestead to the British willingly. He was indicted for treason for undocumented reasons in 1779 but later acquitted.

The Apthorp Mansion, via New York Public Library

Notably, the Apthorp mansion served as a temporary headquarters for George Washington leading up to the September 16, 1776 Battle of Harlem Heights. On September 14, 1776, “in the Apthorp drawing room, Washington and his men planned the operation that would send Nathan Hale to spy on the British on Long Island – which then cost him his life.”

In contrast to accused traitor Apthorp, the Striker family’s loyalty to the American Revolution was not in question. James Striker, the son of Gerrit Striker, fought with General Washington at the Battle of Trenton on Christmas 1776. In 1780, disguised as a yeoman, James returned to Strycker’s Bay to find it in the hands of the enemy. The Redcoats had taken over his family’s home. “The slaves and servant men were driven off and the women compelled for days to cook and attend to the wants of their captors.”

Advertisement

When James died in 1831, the family farmhouse became Striker’s Bay Tavern. Described by Salwen as a “secluded little snuggery,” the Tavern was located “at the foot of a steep lane with a dock and, in later days, a small station of the Hudson River Railroad … the lawn by the river made a fine dance floor, and behind the house there were targets for shooting parties.”

Joseph Francis, inventor of the corrugated metallic life boat and Congressional Gold Medal awardee, served as landlord of the tavern in 1841. According to The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Francis’ tenancy was “memorable for the number of noted personages who assembled there, the likes of which included Edgar Allan Poe and George Pope Morris.

READ MORE: EDGAR ALLAN POE’S TWO YEARS IN AN UPPER WEST SIDE FARMHOUSE

The Striker estate was partitioned in 1855 and sold on June 11, 1856, before it was destroyed by fire in the early 1860s. The fire took with it the family’s Dutch bible and portraits which included one of James Stryker. The Strycker Bay inlet was filled in the 1860s and, like the other UWS villages and settlements, feel victim to urbanization shortly thereafter.

The 96th Street Viaduct was built between 1900 and 1902 “to carry Riverside Drive across the now-filled valley that was Strycker’s Bay.” The shoreline would eventually make way for the Henry Hudson Parkway and Riverside Park, all but ensuring that nothing remains of Strycker’s Bay besides the valley containing W. 96th Street.”