Eleanor Roosevelt relaxes against a boulder, her back to Riverside Park as she overlooks West 72nd Street and Riverside Drive. She is deep in thought. What is this bronzed Eleanor thinking? And what is her connection to the Upper West Side?

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, niece of a president and wife to another, is best known for her dedication to fighting for those who could not fight for themselves. A native New Yorker, she was an active part of the League of Women Voters, the American Red Cross, and the Women’s Trade Union League. She was a defender of worker’s rights and the poor, took on racial injustice, and was the head of the United Nations commission that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. But as far as this writer can tell, none of these things happened in our area of the city.

Despite her deeply ingrained ties to New York and its storied haven for the principles of social justice and equality, Roosevelt’s pre-statue connection to the Upper West Side seems tenuous at best. Historical records of her time in Manhattan prove she lived mostly downtown and on the Upper East Side. She did spend some time at 300 West End Avenue where she met with Harry Belafonte and other civil rights activists. However, the New York Times may have inadvertently identified the most concrete connection.

Speaking of the statue’s location, the Times wrote, “the oak-shaded site is near the spot in Riverside Park where she took her son, the late Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., to see the shantytowns in which people lived during the Depression.” It is, perhaps, only fitting that a perpetual tribute to her stands at this location within a neighborhood famous for its ideals of inclusivity and social progression.

A SHANTY TOWN ALONG THE HUDSON RIVER

When Roosevelt’s statute was unveiled in October 1996, then First Lady Hillary Clinton was the keynote speaker. She mentioned the imaginary conversations she held with Mrs. Roosevelt, a prescient dialogue proven sensical as time had marched on for both former White House residents. “Mrs. Roosevelt represents an untarnished heroine in the fight to house and feed the needy and make the world more civilized. Perhaps for everyone except Mrs. Clinton, it is hard to imagine the ‘I hate Eleanor’ buttons that were the rage among Republicans 60 years ago,” wrote the Times.

Get The Upper West Side Newsletter

The correlation between the two pioneering but polarizing women is hard to miss, as is the importance of each woman to the recognition of women’s rights. As the Times reported in 1996, the legacy of Eleanor Roosevelt struck a chord with many New Yorkers when the statute was unveiled. “When the statue has been uncovered for last-minute polishing, people have stopped to take a look. Some have smiled, some have cried, some have stared through the years at a ceaseless inspiration. An older woman looked and looked, and said she wished she could have a long talk with her. Jenny Feiffer, a writer who brought her two young daughters to see ‘an incredible role model,’ said, ‘She takes on more and more substance the more time goes by.'”

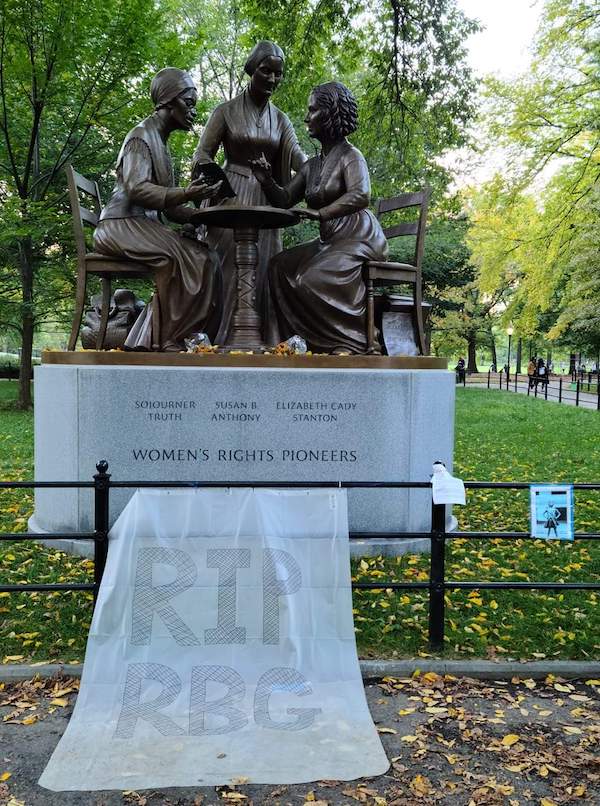

Hillary Clinton was again present for the dedication and posted about its representative importance. After the passing of civil rights icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg, many flocked to the monument to show appreciation to the former Supreme Court Justice, her life’s work made possible by the three women crafted in bronze above her own tributes – Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. (RBG, as she is fondly remembered, now has her own statute in her native Brooklyn, the seventh statute in the city depicting a real woman.)

Both monuments on the Upper West Side – that of Roosevelt and the Women’s Rights pioneers – often become renewed symbols of the struggle for equality when the battle for it takes center stage. Eleanor is frequently topped with the pink hat made famous during the 2017 Women’s March and she is usually decorated in honor of International Women’s Day. Pictures of The Fearless Girl often adorn the Central Park fencing around the real-life pioneering women that came before her. Flowers are routinely left at the foot of each monument, a small but striking reminder of how far we’ve come, how far we need to go, and how grateful some of us are for all of it.

“My voice will not be silent.” After her husband and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt passed away during his fourth term in office in 1945, Mrs. Roosevelt used those words to assure her friends that her work would not end just because her husband’s did. And this brings me back to the original question: what is the UWS statue of Eleanor Roosevelt thinking about?

One day, hopefully not in the too distant future, her ruminative stance will be seen as a prideful one, a content reflection on the realization of goals achieved from a life spent fighting for the underdog. Until then, whatever the real reason may be for the statue’s home, the fact is that the city chose the Upper West Side as host to a memorial dedicated to someone who fought for the greater good. After all, isn’t that one of the million reasons we love the UWS?

Is the artist’s name mentioned and I missed it? Penelope Jencks.

Ever heard of Google?

As a member of the Park Committee of CB7 at the time, I was present for the unveiling of the Roosevelt statue. It was a wonderful, moving ceremony, and Ms. Clinton (whom I got to meet that day) was all class and focus. It was one of the most memorable things I have done as an UWS activist. I pass that statue on my bike at least once a week, and always remember that day.

Didn’t MS Clinton have an actual conversation with MS Roosevelt a few miles north and on the other side of the rive?

Clinton was 15 when Roosevelt died, so if she met her, Clinton would have had to be very young.